[Now, however, President Xi Jinping appears to have altered course, at the same moment that he is building military airfields on disputed islands in the South China Sea, declaring exclusive Chinese “air defense identification zones,” sending Chinese submarines through the Persian Gulf for the first time and creating a powerful new arsenal of cyberweapons.]

By David E. Sanger and William J. Broad

|

| @ The New York Times |

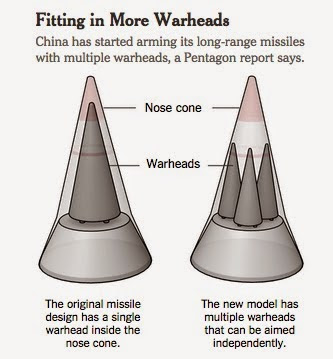

WASHINGTON — After

decades of maintaining a minimal nuclear force,China has

re-engineered many of its long-range ballistic missiles to carry multiple

warheads, a step that federal officials and policy analysts say appears

designed to give pause to the United States as it prepares to deploy more

robust missile defenses in the Pacific.

What makes China’s decision particularly

notable is that the technology of miniaturizing warheads and putting three or

more atop a single missile has been in Chinese hands for decades. But a

succession of Chinese leaders deliberately let it sit unused; they were not

interested in getting into the kind of arms race that characterized the Cold

War nuclear competition between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Now, however, President Xi Jinping appears

to have altered course, at the same moment that he is building military

airfields on disputed islands in the South China Sea, declaring exclusive

Chinese “air defense identification zones,” sending Chinese submarines through

the Persian Gulf for the first time and creating a powerful new arsenal of

cyberweapons.

Many of those steps have taken American

officials by surprise and have become evidence of the challenge the Obama

administration faces in dealing with China, in particular after American

intelligence agencies had predicted that Mr. Xi would focus on economic

development and follow the path of his predecessor, who advocated the country’s

“peaceful rise.”

Secretary of State John Kerry arrived in

Beijing on Saturday to discuss a variety of security and economic issues of

concern to the United States, although it remained unclear whether this

development with the missiles, which officials describe as recent, was on his

agenda.

American officials say that, so far, China has

declined to engage in talks on the decision to begin deploying multiple nuclear

warheads atop its ballistic missiles.

“The United States would like to have a

discussion of the broader issues of nuclear modernization and ballistic missile

defense with China,” saidPhillip C. Saunders,

director of the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs at National

Defense University, a Pentagon-funded academic institution attended by many of

the military’s next cadre of senior commanders.

“The Chinese have been reluctant to have that

discussion in official channels,” Mr. Saunders said, although he and other

experts have engaged in unofficial conversations with their Chinese

counterparts on the warhead issue.

Beijing’s new nuclear program was reported

deep inside the annual Pentagon report to

Congress about Chinese military capabilities, disclosing a development that

poses a dilemma for the Obama administration, which has never talked publicly

about these Chinese nuclear advances.

President Obama is under more pressure than

ever to deploy missile defense systems in the Pacific, although American policy

officially states that those interceptors are to counter North Korea, not

China. At the same time, the president is trying to find a way to signal that

he will resist Chinese efforts to intimidate its neighbors, including some of

Washington’s closest allies, and to keep the United States out of the Western

Pacific.

Already, there is talk in the Pentagon of

speeding up the missile defense effort and of sending military ships into

international waters near the disputed islands, to make it clear that the

United States will insist on free navigation even in areas that China is

claiming as its exclusive zone.

Hans M. Kristensen, director of the Nuclear

Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, a policy research

group in Washington, called the new deployments of Chinese warheads “a bad day

for nuclear constraint.”

“China’s little force is slowly getting a

little bigger,” he said, “and its limited capabilities are slowly getting a

little better.”

To American officials, the Chinese move fits

into a rapid transformation of their strategy under Mr. Xi, now considered one

of the most powerful leaders since Mao Zedong or Deng Xiaoping. Vivid

photographs, which were released recently, of Chinese efforts to reclaim land

on disputed islands in the South China Sea and immediately build airfields on

them, underscored for White House policy makers and military planners the speed

and intensity of Mr. Xi’s determination to push potential competitors out into

the mid-Pacific.

That has involved building aircraft carriers

and submarines to create an overall force that could pose a credible challenge

to the United States in the event of a regional crisis. Some of China’s

military modernization program has been aimed directly at America’s

technological advantage. China has sought technologies to block American

surveillance and communications satellites, and its major investments in

cybertechnology — and probes and attacks on American computer networks — are

viewed by American officials as a way to both steal intellectual property and

prepare for future conflict.

The upgrade to the nuclear forces fits into

that strategy.

“This is obviously part of an effort to

prepare for long-term competition with the United States,” said Ashley J. Tellis, a senior associate at the

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace who was a senior national security

official in the George W. Bush administration. “The Chinese are always fearful

of American nuclear advantage.”

American nuclear forces today outnumber

China’s by eight to one. The choice of which nuclear missiles to upgrade was

notable, Mr. Tellis said, because China chose “one of few that can

unambiguously reach the United States.”

The United States pioneered multiple warheads

early in the Cold War. The move was more threatening than simply adding arms.

In theory, one missile could release warheads that adjusted their flight paths

so each zoomed toward a different target.

The term for the technical advance — multiple

independently targetable re-entry vehicle, or MIRV — became one of the Cold

War’s most dreaded fixtures. It embodied the horrors of overkill and

unthinkable slaughter. Each re-entry vehicle was a miniaturized hydrogen bomb.

Each, by definition, was many times more destructive than the crude atomic

weapon that leveled Hiroshima.

China watched all this from the sidelines.

Gingerly, it improved its warheads and missile forces in what amounted to baby

steps, but chose to field a force that the leadership in Beijing believed could

deter aggression with the smallest number of deployed warheads.

In 1999, during the Clinton administration,

Republicans in Congress charged that Chinese spies had stolen the secrets of

H-bomb miniaturization. But intelligence agencies noted Beijing’s restraint.

“For 20 years,” the C.I.A. reported, “China has had the technical

capability to develop” missiles with multiple warheads and could, if so

desired, upgrade its missile forces with MIRVs “in a few years.”

The calculus shifted in 2004, when the Bush

administration began deploying a ground-based antimissile system in Alaska and

California. Early in 2013, the Obama administration, worrying about North

Korean nuclear advances, ordered an upgrade. It called for the interceptors to

increase in number to 44 from 30.

While administration officials emphasized that

Chinese missiles were not in the system’s cross hairs, they acknowledged that

the growing number of interceptors might shatter at least some of Beijing’s

warheads.

Today, analysts see China’s addition of

multiple warheads as at least partly a response to Washington’s antimissile

strides. “They’re doing it,” Mr. Kristensen of the Federation of American

Scientists said, “to make sure they could get through the ballistic missile

defenses.”

The Pentagon report, released on May 8, said

that Beijing’s most powerful weapon now bore MIRV warheads. The

intercontinental ballistic missile is known as the DF-5 (for Dong Feng, or East

Wind). The Pentagon has said that China has about 20 in underground silos.

Private analysts said each upgraded DF-5 had

probably received three warheads and that the advances might span half the

missile force. If so, the number of warheads China can fire from that weapon at

the United States has increased to about 40 from 20.

“It’s been a long time coming,” said Jeffrey Lewis, an expert on Chinese nuclear

forces at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey. In an

interview, he emphasized that even fewer of the DF-5s might have received the

upgrade.

Early last week, Mr. Kristensen posted a public

report on the missile intelligence.

Beijing’s new membership in “the MIRV club,”

he said, “strains the credibility of China’s official assurance that it only

wants a minimum nuclear deterrent and is not part of a nuclear arms race.”