[As nearly 200 nations struggle

over global climate negotiations, the world’s two biggest polluters sign an

agreement, but it was short on details.]

The pact between the world’s two

biggest polluters came as a surprise to the thousands of attendees gathered

here for a United Nations climate summit. China and the United States, rivals

that face growing tensions over trade, human rights and other issues, spoke as

allies in the fight to keep global warming to relatively safe levels.

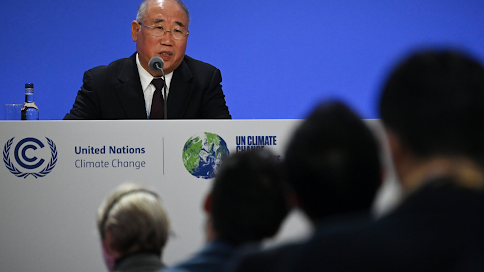

“We both see the challenge of

climate change is existential and a severe one,” said Xie Zhenhua, China’s

climate change envoy. “As two major powers in the world, China and the United

States, we need to take our due responsibility and work together and work with

others in the spirit of cooperation to address climate change.”

John Kerry, the U.S. special envoy

for climate, followed the remarks from Mr. Xie with an assessment of his own.

“The U.S. and China have no shortage of differences,” said Mr. Kerry, a former

secretary of state with a long history of negotiating with the Chinese. “But on

climate, cooperation is the only way to get this job done.”

Still, the joint agreement was

short on specifics. It did not extract a new timetable from China under which

the country would ratchet down emissions, nor did China set a ceiling for how

high its carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases would reach before they

started to fall. China agreed to “phase down” coal, the dirtiest fossil fuel,

starting in 2026, but did not specify by how much or over what period of time.

The announcement from China and the

United States came on the same day that summit organizers issued an initial draft of a new global agreement to fight

climate change that called on countries to “revisit and strengthen” by the end

of 2022 plans for cutting greenhouse gas emissions and to “accelerate the

phasing-out of coal and subsidies for fossil fuels.”

The language on coal and government

fossil fuel subsidies would be a first for a U.N. climate agreement if it stays

in the final version.

Yet many countries and

environmentalists said the rest of the document was still too vague on crucial

details like what sorts of financial aid richer nations should provide poorer

ones struggling with the costs of climate disasters and adaptation.

The draft “is not the decisive

language that this moment calls for,” said Aubrey Webson, chairman of the

Alliance of Small Island States, a group of countries that are among those most

threatened by climate change.

Scientists have said that nations

need to cut global emissions from fossil fuels roughly in half this decade to

keep average global temperatures from rising beyond 1.5 degrees Celsius, or 2.7

degrees Fahrenheit, compared with preindustrial levels. Beyond that threshold,

the risks of deadly heat waves, droughts, wildfires, floods and species

extinction grow considerably. The planet has already warmed 1.1 degrees

Celsius.

Negotiators here from nearly 200 countries

are likely to demand significant changes to the draft as the talks enter their

last, most difficult stretch. By tradition, a new global agreement requires

every party to sign on. If any one nation objects, talks can deadlock.

The British prime minister, Boris

Johnson, returned to Glasgow on Wednesday to urge countries to set aside

differences and strike a deal. “The world has heard leaders from every country

stand here and acknowledge the need for action,” he said. “And the world will

find it absolutely incomprehensible if we fail to deliver that.”

But persuading nations around the

world, many of which depend on fossil fuels for energy and have their own

internal politics and vested interests, to move in a new direction is a

herculean challenge.

Mr. Kerry said countries had no

choice but to work together. “This is not a discretionary thing,” he said.

“This is science, it’s math and physics that dictate the road we have to

travel. And we cannot reach our goal unless everyone works together.”

Several experts said the joint pact

between China and the United States fell short of a 2014 deal between the

United States and China to jointly curb emissions, which helped spur the Paris

climate agreement among nearly 200 nations a year later.

“While this is not a game changer

in the way the 2014 U.S.-China climate deal was, in many ways it’s just as much

of a step forward given the geopolitical state of the relationship,” said Thom

Woodroofe, a former climate diplomat and a fellow at the Asia Society Policy

Institute working on United States-China climate cooperation. “It means the

intense level of U.S.-China dialogue on climate can now begin to translate into

cooperation.”

The agreement won praise among

leaders and diplomats at the climate summit, who said they hoped it would

inject fresh energy into the global negotiations aimed at keeping global

temperatures from rising to dangerous levels. With just days remaining before

the summit ends, negotiators are working late into the night to try to hammer

out a global accord that, they hope, can satisfy every country — no easy

task.

Small island states like the

Maldives, which has been inhabited for thousands of years but is projected to

be swamped by rising seas within generations, want all countries to slash

emissions as fast as possible. Oil and coal producers like Russia and Australia aren’t

as eager to rapidly phase out fossil fuels. And large developing countries

like India

are holding out for financial help to shift to cleaner energy.

There are four major areas of

contention as negotiators try to reach a deal before the summit ends on Nov.

12.

Speeding Up Emission Cuts

Under the landmark Paris

climate agreement of 2015, every nation agreed that humanity should limit

global warming to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above

preindustrial levels while “pursuing efforts” to hold warming to just 1.5

degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit).

To reach that target, each nation

agreed to submit its own plan to shift away from fossil fuels and to curb

deforestation, and to update those plans every five years. While everyone

agreed that the initial pledges put forward in Paris were insufficient, the

hope was that, over time, nations would ratchet up action and get closer to the

goal.

But there are a few big problems.

First, the ratcheting process has

been slow and uneven. Ahead of the Glasgow summit, most countries submitted

new pledges to curb their emissions between now and 2030. Some, like

the United States and European Union, vowed to make deeper cuts this decade.

But others, such as Australia, Brazil and Russia, barely strengthened their

short-term plans.

When analysts added up the

short-term pledges, they found that the world was likely on track to heat up

around 2.4 to 2.7 degrees Celsius this century. That’s an

improvement over Paris, but it would still increase the likelihood of climate

catastrophes that could exacerbate hunger, disease and conflict.

On top of that, many of the

countries most vulnerable to climate change, such as Ethiopia and Bhutan, want

the world to keep to the stricter target of 1.5 degrees Celsius, or else they

will face unmanageable disasters.

“1.5 degrees is what we need to

survive,” Mia Mottley, prime minister of Barbados, said last week. “Two degrees

is a death sentence for the people of Antigua and Barbuda, Maldives, Domenica,

Fiji, Kenya, Mozambique, Samoa and Barbados.”

How to speed up climate efforts

remains a source of debate.

Many vulnerable countries want countries to

come back to the United Nations annually with stronger plans until the world is

on track for 1.5 degrees Celsius. Currently, countries aren’t expected to

update their plans until 2025, which some fear could be too late.

But that proposal faces opposition

from fossil fuel producers like Saudi Arabia and Russia. And there’s not even

consensus that 1.5 degrees should be the official goal: The United States and

the European Union have supported focusing on that stricter target, but some

major emitters like China have balked.

Where’s the Money?

Money has long been a big sticking

point in the global fight against climate change, and tensions over

the topic have flared again in Glasgow.

President Biden and European leaders

have insisted that developing countries such as India, Indonesia or South

Africa need to accelerate their shift away from coal power and other fossil

fuels. But those countries counter that they lack the financial resources to do

so, and that rich countries have been stingy with aid.

A decade ago, the world’s

wealthiest economies pledged to mobilize $100 billion per year in climate

finance for poorer countries by 2020. But they have fallen short

by tens of billions of dollars annually.

At the same time, little climate

aid to date has gone to help poorer countries cope with the hazards of a hotter

planet, such as sea walls or early-warning systems for floods and droughts.

Vulnerable nations are warning that

they need far more help to survive. A group of African nations, along with

China, India and Indonesia, has asked for as much as $1.3 trillion a year after 2025, That

dwarfs anything that wealthy countries have been willing to propose so far.

‘Loss and Damage’

Even as vulnerable countries plead

for more climate aid, they have asked for separate compensation for climate

damages that they can’t adapt to. And they argue that wealthy nations like the

United States and the European Union, which are historically responsible for most of the extra greenhouse

gases now heating the atmosphere, should pay. This issue is known as

“loss and damage.”

“Lots of people are losing their

lives, they are losing their future, and someone has to be responsible, and

those people need to be compensated,” said A.K. Abdul Momen, the foreign

minister of Bangladesh.

Richer countries have, however,

historically resisted calls for a specific funding mechanism for loss and

damage, fearing that it could open the door to a flood of liability claims.

Only the government of Scotland has been willing to offer specific dollar

amounts, pledging $1.4 million last week for victims of climate

disasters.

Regulating Carbon Markets

One of the thorniest issues is how

to regulate the fast-growing global market for carbon offsets. The Paris

agreement urged clearer rules on this topic back in 2015, but negotiators have

been unable to agree on the extremely dense and technical subject.

Carbon offsets allow countries or

businesses to compensate for their own emissions by paying for mitigation

elsewhere. But it raises tricky questions about accounting, transparency and

verification.

Some climate advocates said they

would prefer negotiators to leave Glasgow without a resolution on these issues

rather than with weak rules.

“No point in accepting phony carbon

credits into the system, which would directly increase warming,” wrote Mohamed

Adow, director of Power Shift Africa, a research institute in Kenya.

Developing countries have also

called for a percentage of proceeds from all carbon credit trades to be set

aside for an adaptation fund. But the European Union has criticized this idea, calling it a “mandatory

international tax.”