[Wealthy countries have already grabbed a major chunk of the available supply. The United States, the United Kingdom, Japan and Canada have struck deals large enough to vaccinate their entire populations. By contrast, a pooled global effort to distribute vaccines equitably to more than 150 countries — including dozens of low-income nations — has secured only 700 million doses.]

NEW DELHI — Adar Poonawalla is an Indian billionaire whose family-owned firm makes more vaccines a year than any other company on Earth. Ask him about the race for a coronavirus vaccine and he will offer some unvarnished opinions.

One

prominent vaccine candidate requiring ultra-cold storage is “a joke” that will

not work for the developing world. Anyone who declares how long a vaccine will confer

immunity is talking “nonsense.” The world’s entire population will not be

immunized until 2024, he says, contrary to rosier predictions.

Poonawalla

is equally frank about the gamble his company, Serum Institute of India, is

making in the pandemic. He is putting $250 million of his family’s fortune

into a bid to ramp up manufacturing capacity to 1 billion doses through

2021.

“I

decided to go all out,” said Poonawalla, 39. Among the initial skeptics: his

father, Cyrus, the company’s founder. “He said: ‘Look, it’s your money. If you

want to blow it up, fine.’ ”

It

is a bet with global repercussions. In the quest for effective coronavirus vaccines, India is poised to play a

critical role in supplying the developing world, which is starting the race

with a distinct disadvantage.

Wealthy

countries have already grabbed a major chunk of the available supply. The United States, the

United Kingdom, Japan and Canada have struck deals large enough to vaccinate

their entire populations. By contrast, a pooled global effort to distribute

vaccines equitably to more than 150 countries — including dozens of low-income

nations — has secured only 700 million doses.

Pfizer,

which announced stellar

early results for its vaccine candidate Monday, has struck very few

deals to supply its product to developing countries. Pfizer’s vaccine must also

be stored at ultra-low temperatures, a major challenge in much of the world.

[The

top coronavirus vaccines to watch]

Rich

nations are “all cutting in line and hoarding vaccine supply to immunize as

many people as possible, even if this leaves other countries unable to immunize

those at highest risk,” said Nicholas Lusiani, a senior adviser at Oxfam

America, a nonprofit group devoted to fighting poverty.

Enter

Indian vaccine makers, led by Serum Institute, the largest manufacturer in the

world by volume. Well before the pandemic, India was a “vaccine powerhouse”

specializing in affordable exports to low- and middle-income countries, said

Andrea Taylor, an assistant director at the Duke Global Health Innovation

Center.

Taylor

said countries such as Brazil and China also have manufacturing capacity, but

she singled out Indian vaccine makers because they moved so quickly to form

tie-ups with global companies and increase their own production. India is

“going to be the absolute star in the story,” she said.

Anthony

S. Fauci, the top infectious-disease specialist in the United States, shared

that sentiment during

a panel earlier this year. India’s manufacturing capability is “going to be

very, very important” as effective vaccines emerge, he said

Four

major pharmaceutical companies — AstraZeneca, Novavax, Johnson & Johnson and Sanofi — have reached

agreements to eventually produce at least 3 billion vaccine

doses for low- and middle-income countries, according to an analysis of

publicly available data by Airfinity, a research firm in the United Kingdom.

Serum Institute is set to manufacture more than two-thirds of those doses.

Some

of the agreed-upon supply to low- and middle-income countries will come through

the pooled initiative backed by the World Health Organization, known as the

Covid-19 Vaccines Global Access Facility, or Covax. Covax includes higher- and

lower-income countries, more than 150 in total. The United States declined to

join.

Covax

is being co-led by Gavi, a nonprofit vaccine alliance. In September, Gavi

announced a partnership with the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to pay Serum

Institute in advance for 200 million vaccine doses, at a cost of $3 each,

to be distributed in developing countries, hopefully in early 2021. The

$600 million infusion will help Serum ramp up production.

Gavi

and the Gates Foundation “want to assure vaccine supply at an affordable

price,” said Poonawalla, Serum’s chief executive. His aim, meanwhile, is to

cover some of his costs. “At least my risk is taken away so I can sleep at

night,” he said.

The

partnership with Serum, given its size, is “crucial” to Gavi’s larger goal of

ensuring that no country is left behind in the quest for vaccines, said Dominic

Hein, who works on Gavi’s efforts to make vaccines more readily available in

low-income countries.

Under

the agreement, more than 60 countries — largely in Africa and Asia — would

receive the vaccine developed by Oxford University and AstraZeneca or the

vaccine under

development by Novavax.

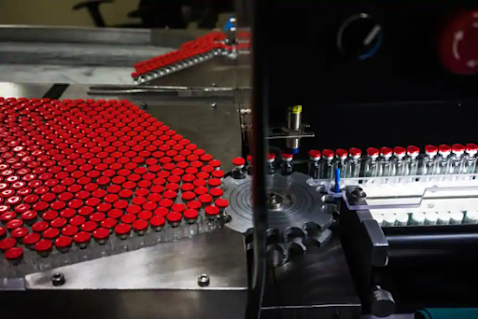

Serum

Institute has struck deals to manufacture both vaccines, which are in Phase 3

trials. It has also inked deals to make two other vaccines, developed by the

American biotechnology company Codagenix and Britain’s SpyBiotech, and is

working on its own vaccine candidate that it hopes will enter trials late next

year. While the Indian company has reached manufacturing agreements with

American companies such as Novavax and Codagenix, it is not currently exporting

its vaccines to the United States.

India

has recorded the second-highest number of coronavirus cases in the world — more

than 8.5 million. Those numbers mean India is a crucial market for future

vaccines and an effective place to test them.

Advanced

clinical trials of three vaccine candidates are underway in India: the

AstraZeneca vaccine and vaccines developed by two Indian pharmaceutical

companies, Zydus Cadila and Bharat Biotech. An Indian company is also starting

clinical trials of Russia’s vaccine candidate, Sputnik V.

“Whether

India makes a vaccine by itself or not, from a manufacturing standpoint, it’s

going to be playing a very, very important role,” said Mahima Datla, managing

director of Biological E., a 67-year-old vaccine producer based in the city of

Hyderabad. Datla also sits on the board of Gavi.

India’s

health minister recently predicted that the country would be in a position to

start distributing a vaccine within

the next six months. The government is working on a plan to immunize

as many

as 250 million people by July, he said.

Reaching

that goal will require the manufacturing heft of Serum Institute. The company

has diverted capacity from existing vaccines and started work on a new

production facility to be completed next year at its headquarters in the

western Indian city of Pune.

Poonawalla

said the company has pledged to keep half of the vaccines it makes for use

within India. It has already begun manufacturing the AstraZeneca vaccine, he

said. About 20 million doses have been made, and he expects to have 10

times that amount ready in the next four months.

He

is optimistic that in 2021, a new coronavirus vaccine will be licensed for

public use every couple of months. “That’s the good news,” Poonawalla said. The

less-good news is that it remains unclear which vaccine, if any, will offer

long-term protection from the virus. “Nobody wants a vaccine that is only going

to protect you for a few months,” he said.

Read

more

Nearly

700 coronavirus-positive women gave birth at a single hospital. Here’s what it

learned.

As

coronavirus cases soar, India’s hospitals race to secure badly needed oxygen

The

17-member family that lived together, ate together and got coronavirus together