[Yet Suu Kyi has watched her relationship with the generals deteriorate while she grows internationally isolated, dragging her heels and fumbling in response to the crackdown. Her preferred tactic of outsourcing the Rohingya issue to a growing number of commissions with international representation, including one led by the late United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan, has been widely criticized, while Rohingya languish in Bangladesh and those left in Myanmar find their access to humanitarian aid, food and resources waning.]

By Shibani Mahtani, Reporter Wai

Moe

SINGAPORE

— A year ago, the Myanmar military embarked on

a sweeping crackdown in restive Rakhine state — driving out almost a million

Rohingya to Bangladesh and creating one of the world’s largest refugee camps

while allegedly raping women, killing children and beheading men in the

process.

Today, even as sanctions mount and the U.S.

State Department and United Nations ready reports that are likely to detail the

military’s premeditated efforts at effectively ridding the state of Rohingya

Muslims, generals remain defiant. They believe they essentially eliminated a

threat that was “growing bigger and bigger,” according to one account of

conversations top military leaders have had with counterparts from Southeast

Asia.

“There was a sense that their problem in

Rakhine had been solved, that this was their solution,” said a person familiar

with the conversations, who declined to be named because of the sensitivity of

the issue. The militants, the military alleged, had embedded in villages and

towns, and they had to be stopped.

“They stand by their actions,” the person

added.

Interviews with a half-dozen former Myanmar

generals and those familiar with their thinking say they have also grown

irritated by civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi’s efforts to quell international

outrage — believing she defends them in public while working to undermine them

by driving sanctions in private.

“Our relationship with the army is not that

bad,” Suu Kyi said Tuesday at a rare address here defending her government’s

handling of the crisis. The generals in her cabinet, she added, are “quite

sweet.”

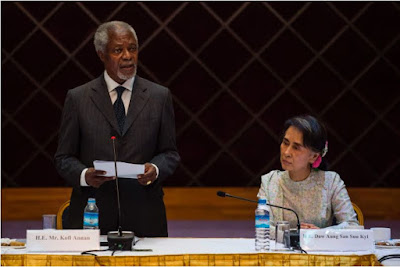

Yet Suu Kyi has watched her relationship with

the generals deteriorate while she grows internationally isolated, dragging her

heels and fumbling in response to the crackdown. Her preferred tactic of

outsourcing the Rohingya issue to a growing number of commissions with

international representation, including one led by the late United Nations

Secretary General Kofi Annan, has been widely criticized, while Rohingya

languish in Bangladesh and those left in Myanmar find their access to humanitarian

aid, food and resources waning.

“We are still hopeless,” Kyaw Hla Aung, a

Rohingya lawyer living in a camp outside Sittwe, Rakhine state’s capital, said

in a phone interview. He and other Rohingya say security forces have arrived in

droves ahead of the conflict’s one-year mark, while doctors and aid workers have

not been seen for weeks.

This was not the reality Suu Kyi envisioned

in May 2016, her second month as the de facto leader of Myanmar’s civilian

government, when she approached Annan to lead a commission looking into the

root of the Rakhine conflict. The commission was to come up with

recommendations into how peace would be achieved in Rakhine state, where

communal violence had erupted in 2012, driving 140,000 Rohingya Muslims into

squalid camps. Members of the maligned minority group say they are native to

Myanmar but were excluded from a junta-era citizenship law, denied rights and

freedom of movement and rendered vulnerable as targets of extreme

discrimination and violence.

Annan, commission members said, negotiated

for months with Myanmar’s government to ensure he had a strong mandate — the

ability to fundraise independently, travel unencumbered around Rakhine state

and Myanmar and have staff within the country.

“We traveled widely, all the way from

Maungdaw in the north to Ngapali in the south,” said Laetitia van den Assum, a

member of the commission and a former Dutch ambassador to Thailand. “Annan

wrote to the government to ensure the commission was not just a useful shield

for them. We wanted to be taken seriously.”

In her address Tuesday, Suu Kyi paid tribute

to Annan, who died last week, for his commitment to the issue.

He “abided by his decision to help us, even

after events in Rakhine brought down severe criticism on Myanmar,” she said,

noting Annan made time to speak to her over the phone periodically on the

challenges her government was facing.

On Aug. 24 last year, after over 150

consultations and meetings, the commission presented its final report at a news

conference in Yangon. It included 88 recommendations on issues including

citizenship for the Rohingya, freedom of movement and education, and spelled

out how these should be implemented.

“There is no time to lose. The situation in

Rakhine state is becoming more precarious,” Annan said at the time.

Just eight hours after he spoke, Rohingya

militants allegedly staged 30 attacks on Myanmar police posts in northern

Rakhine state, according to the Myanmar military, prompting it to embark on a

“clearance operation,” sometimes with the help of armed Rakhine villagers.

Hundreds of Muslim villages were torched, and thousands were killed, and an

estimated 800,000 others hastily gathered their possessions and trekked across

the border to Bangladesh.

The Myanmar military and Suu Kyi’s government

were quick to deny allegations of ethnic cleansing. On Tuesday, she repeated

“terrorist activities” were the initial cause of the events that led to the

crisis in Rakhine state, and that the threat of terrorism remains.

Diplomats and aid workers in Myanmar,

however, said they had seen what looked like preparations for a large-scale

operation in the weeks leading up to the campaign. Security forces were

limiting the quantity of food available to Rohingya families, according to an

internal report shared with The Washington Post. Troops entering the area

confiscated kitchen knives and sticks from households.

Suu Kyi, aware of international pressure in

the wake of the violence, asked a new advisory board to implement the Annan

commission’s recommendations. It would be led by Surakiart Sathirathai, a

veteran Thai politician.

Among those asked to join was Bill

Richardson, a former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and governor of New

Mexico, who was an old friend of Suu Kyi’s.

“She told me that this would be a small group

of internationally acclaimed people who would help implement the Annan

commission’s report,” said Richardson in an interview.

Richardson agreed, stressing he was to have a

free hand, but was concerned by the change in tone he detected in the Nobel

laureate.

“I told her the [commission’s report] doesn’t

make her look good, and she started launching into it. She said, ‘Everybody is

against me, Bill, the human rights groups, your country,’” he recounted.

Giving the board a free rein was never her

intention, said Richard Horsey, a longtime Yangon-based political analyst.

Within weeks of the board’s first meeting in

Naypyidaw, Myanmar’s capital, this January, Richardson quit.

“She’s in denial, and she’s not serious about

dealing with this issue,” he said of Suu Kyi. “Anything that involves taking on

the military, she won’t do. She’ll just do some PR moves like these

commissions.”

Other members found their hands similarly

tied. Kobsak Chutikul, a retired Thai lawmaker and diplomat who quit the board

in July, said he often spent his own money to travel around the country,

refusing to wait for a green light from the capital.

“It was a bit haphazard, because the Annan

commission had their own funding, and we didn’t,” Kobsak said.

Later, government officials in Naypyidaw

started making monthly financial transfers of approximately $15,000 to Bangkok

to support the work of the board, including renting an office space, but none

has been rented for at least half a year. There has been no request yet for

accounting or a return of this money, a board member said.

Myanmar government officials overseeing the

board and its funding did not respond to requests for comment.

Last Thursday, Surakiart was summoned to

Naypyidaw. He submitted the advisory board’s final report, and it was

dissolved, making way for yet another body, a commission of inquiry into the

wrongdoings in Rakhine state.

In a news conference last week, its chairman,

a Philippine diplomat named Rosario Manalo, said there will be “no blaming of

anybody” though the commission was ostensibly set up to pursue accountability.

“This just goes on and on. Next year it will

be another commission, another board,” Kobsak said. “It is all for show — there

is nothing real. It is a hoax.”

The commissions were formed “to find a

solution to the Rakhine crisis which will be acceptable at home and abroad,”

said Zaw Htay, a spokesman for the Myanmar government. Suu Kyi in her address

made a point of highlighting the work of the commission of inquiry, which she

said will start work next week.

Still, the Myanmar military has rebuffed even

Suu Kyi’s small efforts to look into its conduct in Rakhine state. Any

punishments for wrongdoing, said a former high-ranking general, speaking on the

condition of anonymity because he is not authorized to speak to the press, are

to be handled by the military without civilian interference.

The Myanmar government has promised to

resettle the hundreds of thousands of refugees now in Bangladesh and to close

the existing camps in Rakhine state, as an indication to those in Bangladesh

that it is safe to return.

But humanitarian access remains dire for the

Rohingya, and aid agencies have been unable to freely access communities in

northern Rakhine state. UNHCR and UNDP submitted requests for travel

authorizations to visit conflict-hit areas on June 14 and are still waiting for

responses. Large teams on the ground are languishing in hotels and field

offices, unable to do their jobs.

Aung Tun Thet, who coordinates the Myanmar

government’s humanitarian and development work in Rakhine state, said the

authorizations are in the process of being issued but the local situation

“remains fluid” and “risky.”

“The Myanmar government isn’t trustworthy.

They never do what they promise about Rohingya people. They have been cheating

us for decades,” said Muhammad Saeed, a Rohingya community leader in Sittwe.

“Rohingya from Myanmar [have a] message for their friends and family who fled

to Bangladesh,” he said. “It would be like stepping into hell if you came back

to Myanmar.”

Wai Moe reported from Yangon, Myanmar.

Read

more: