[The insurgents have continued to gain far-flung territory and launch devastating urban attacks, even as the U.S. government embarks on a new initiative to strengthen and expand the Afghan defense forces, bringing in thousands of new U.S. military trainers in close cooperation with Ghani and his security advisers.]

By Pamela Constable

|

|

Afghans

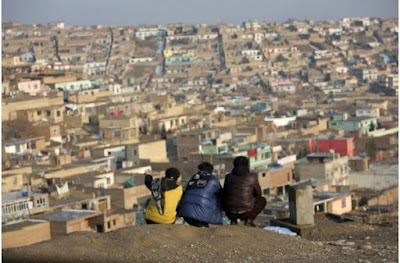

look over Kabul in January. (Rahmat Gul/AP)

|

KABUL — The streets are clogged with yellow taxis

again. Peddlers are back pushing carts of shampoo and socks, sidewalk juice

sellers are crushing pomegranates, and pigeons are pecking at corn outside a

riverside shrine. The evidence of the Afghan capital’s bloodiest week in eight

months has been scrubbed away.

But the city still has not fully recovered.

It is not only the shock of triple terrorist

attacks that took 150 lives within 10 days last month — an ambulance-borne

suicide bomb, a hilltop raid on a luxury hotel and a commando attack on a

military academy. It is not only the visible heightening of security that

followed — armed men on corners, roads blocked for official convoys and

turreted military vehicles parked outside foreign and government compounds.

It is something else in the frigid winter air —

a deeper sense of anxiety that things are out of control, that the government

is failing to serve the public and consumed by political power struggles.

People fear the destructive menace of the Taliban and the Islamic State, but

their anger is directed at leaders, especially President Ashraf Ghani, who many

feel have abandoned them.

“People did not suddenly become afraid, but

this time the violence has added to their frustrations with the government. It

showed a total failure of institutions and leadership,” said Haroun Mir, an

independent analyst and former government security adviser.

Like several observers, Mir said Afghans feel

increasingly frustrated with the National Unity Government, which they see as

preoccupied with combating domestic political opponents and courting

international favor, while many ordinary citizens can’t find jobs or feel safe

walking the streets.

“Security has become the privilege of the

elite,” he said. “The rest of us are in the hands of God.”

The insurgents have continued to gain far-flung

territory and launch devastating urban attacks, even as the U.S. government

embarks on a new initiative to strengthen and expand the Afghan defense forces,

bringing in thousands of new U.S. military trainers in close cooperation with

Ghani and his security advisers.

In west Kabul, where so many mosques have been

attacked in the past year that some are now guarded by local militiamen and

others have closed, people are especially nervous and disillusioned.

“This government is destroying itself and the

country,” said Khudadad Allahyar, 65, a resident of Dasht-e-Barchi, a district

of west Kabul dominated by Shiite ethnic Hazaras. “When we leave home to go and

pray, we are not sure we will come back safely.”

Ghani has responded swiftly to the recent spate

of terrorist attacks, although with mixed results. He visited survivors in

hospital wards and announced the removal of numerous police and military

officials. But he also offered contradictory remarks by giving an emotional

speech at a mosque about “avenging” the violence followed by a televised

lecture about the urgency of seeking reconciliation with the Taliban.

Several of Ghani’s aides said he remains

focused on his other top priorities as well as the insurgent threat. One

priority is reforming a public sector known for bloat and corruption; another

is preparing for local, parliamentary and then presidential elections in the

coming months. But that process has been marred by technical and political

problems, and last week officials announced that the first polls slated for

July probably will be delayed until October.

“The brutality and lives lost in the Kabul

attacks created a psychosis of fear, and people are full of anxiety, but this

has not distracted the president and his team from the broader agenda,” said a

senior aide to Ghani, speaking on the condition of anonymity to talk freely.

“If we can pass through this crisis, the government will be back on track, and

the electoral season will be healthier.”

The other issue challenging Ghani’s authority

is public fights between the president and current and former officials that

have dominated headlines for weeks. Such power struggles, instead of being

handled through negotiations, have threatened to politicize intelligence

agencies, pit regional strongmen against the central government and potentially

divide the national defense forces.

“These political distractions are becoming more

dangerous than the Taliban,” said Javid Faisal, a senior aide to the government’s

chief executive officer, Abdullah Abdullah, who ran against Ghani in 2014 but

later agreed to share power with him after a fraud-plagued and inconclusive

election. “You expect the Taliban to act like terrorists, but you don’t expect

friends to behave like enemies.”

The most potentially destabilizing quarrel is

with Atta Mohammad Noor, a wealthy former militia leader and longtime governor

of Balkh province in the north. After months of negotiations in which Atta

demanded more official perks and power, Ghani abruptly fired him in December. Atta

refused to resign, and the president threatened to dislodge him by force until

he was dissuaded by the White House.

Now, a tense stalemate reigns. Atta remains at

his post, and his political party — which dominates the security forces and

backed Abdullah for president — is vacillating between the two camps.

Critics blame Ghani for needlessly humiliating

a powerful and vengeful rival whom he could have appeased with blandishments,

while his supporters blame Atta — who threatened to lead violent protests when

Ghani claimed victory in 2014 — for behaving like a warlord while reaping the

benefits of a modern democratic order.

“This situation sucked the energy out of the

government for a couple of weeks, but it also indicates that the state is

slowly hardening,” said the senior aide to Ghani. “The governor was scared he

would lose the wealth and power he had acquired illegally.” Only several wrong

signals from the United States, the aide said, made Atta feel he could tough

things out, but the de facto governor has lost crucial popular support and may

now be fatally weakened.

The second, newer brouhaha is between Ghani and

another high-profile opponent, Rahmatullah Nabil, who quit as head of the

national intelligence agency two years ago in a policy dispute with Ghani and

since then has co-founded an opposition party. Nabil, who recently accused

Ghani of fraudulently manipulating the 2014 election, suddenly was barred from

returning to Afghanistan while visiting the United States last month. Since

then, officials have denied imposing such a bar, but Nabil has extended his

trip abroad, and aides said his plans are not decided.

These fights, while providing endless talk show

fodder, also have added to concern that Afghan leaders are more worried about

undermining each other as potential electoral rivals than about restoring public

confidence and strengthening a democratic system that still is floundering

badly after 17 years. Many Afghans fear presidential elections will not be held

at all by next year, defying the constitution and public demand.

“The government is not sincere about reforms.

The elite officials live in fortresses and have families and houses abroad.

They don’t feel what real people do,” said Mir, the analyst. The Ghani

administration, he charged, is more concerned with placating its Western

backers and consolidating power than addressing public concerns. “Ghani is

trying to divide and rule, when what Afghanistan needs is to be united. It

might help him for now, but it could destroy the country.”

Sharif Hassan contributed to this report.

Read

more