[Many Afghans report that concerted harassment

and discrimination by the Pakistani authorities have become too much to bear.

And Pakistan has flatly given undocumented Afghans a Nov. 15 deadline to obtain

legal documents like passports and visas — a near impossibility for most – or

face arrest and deportation, which could lead to even greater numbers leaving

Pakistan in the coming weeks.]

By Rod Nordland

|

|

A

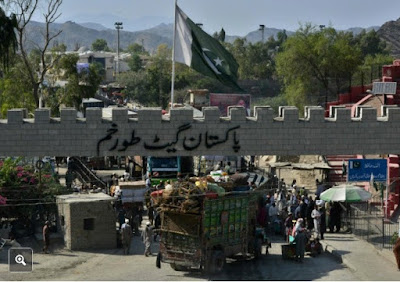

truck carried the belongings of a repatriated Afghan refugee family across

the

border with Pakistan into Afghanistan in September. Credit

A Majeed/Agence

France-Presse — Getty Images

|

SAMARKHEL,

Afghanistan — There is one

country in the world that is now taking in more Afghan migrants than all the

countries in Europe and South Asia put together this year.

That would be Afghanistan itself.

By the end of the year, aid officials here

expect some 1.5 million migrants to return to Afghanistan — many of them

forcibly, and including some officially registered as refugees.

Some will come from Europe, which has

recently signed a deal with Afghanistan to return tens of thousands of migrants

who were not granted asylum. A far larger amount are being forced back by Iran

and, particularly, Pakistan, where the United Nations says there are 1.3

million registered Afghan refugees and an additional 700,000 undocumented

Afghans.

Many Afghans report that concerted harassment

and discrimination by the Pakistani authorities have become too much to bear.

And Pakistan has flatly given undocumented Afghans a Nov. 15 deadline to obtain

legal documents like passports and visas — a near impossibility for most – or

face arrest and deportation, which could lead to even greater numbers leaving

Pakistan in the coming weeks.

The last straw for Ghulamullah, a father of

10 who had sons in Pakistani schools and one married to a Pakistani woman, was

when a soldier entered his house with a dog. “I came to Pakistan to save my

honor and my religion,” he said, “but I see there is no more honor in Pakistan.

The Pakistani Army gave me 15 days to leave.” He has now settled in a camp near

Jalalabad, in eastern Afghanistan.

Official or unofficial, many of the Afghans

have lived abroad for decades, and they are now returning to a country where

the war is at its most traumatic since 2001. And as they come back, they are

redrawing the demographic map of a region that has long been defined by its displaced

population and where cities are already straining to deal with rapidly

expanding tent camps and shanty towns.

“With all these returns from Pakistan and

Iran as well, and looming returns from Europe, it’s a perfect recipe for a

perfect storm because that puts a strain on the capacity of the government to

respond,” said Laurence Hart, head of the International Organization for

Migration office in Kabul.

Aid groups do not have budgets to care for

many of the new arrivals, who are expected in many cases to end up swelling the

ranks of the internally displaced — people who have lived often for years in

squalid conditions in camps around cities. “It’s a poverty competition here

now,” Mr. Hart said. “Existing I.D.P.s are increasingly vulnerable because of

new arrivals.” I.D.P. stands for internally displaced people.

Within Afghanistan, the worsening war with

the Taliban has sent record numbers of people fleeing their homes in conflict

areas. Just in the past two months, according to Afghanistan’s Ministry of

Refugees and Repatriation, 600,000 people have been displaced from their homes

by conflict, swelling the ranks of the 1.2 million internal refugees or

displaced people in Afghanistan from previous years to as much as 1.8 million.

That could mean more than three million

internal or returning refugees inside the country, more than Afghanistan has

ever before experienced. Many of them will have nowhere to go, pitching up at

existing camps, making new settlements, and crowding into already overcrowded

villages — since few of the returnees can go back to their original homes,

often in war-torn areas that they left decades ago.

Add to that mix, programs have quietly ramped

up in recent months to return Afghans from Europe who are judged ineligible for

asylum there.

Norway this year has sent back 442 Afghans,

more than half of them forcibly, while Germany has returned 2,900 Afghans,

nearly all voluntarily. Early in October, the European Union signed an

agreement with Afghanistan to return Afghans whose asylum appeals are rejected

— most likely resulting in tens of thousands of repatriations. Known as the

Joint Way Forward declaration, which critics say Europe made a condition of

continued development assistance to Afghanistan, it even provides for building

a dedicated airport terminal in Kabul to handle the expected repatriations.

Many of those returning are people who have

spent many years and even decades in their host countries, including many cases

of people born there who are now adults with children of their own.

“I don’t remember a time this difficult,”

said Maya Ameratunga, the Afghanistan director for the United Nations High

Commissioner for Refugees, or UNHCR. She had previously worked in Pakistan.

“Now we’re dealing with the population who left Afghanistan in the 1980s and

don’t know this country.”

Every morning now a parade of trucks loaded

15 feet high with household possessions, firewood and small children — and even

sometimes a cow or two — pulls up at the Samarkhel Encashment Center outside

Jalalabad. The center is run by the UNHCR, and catches the traffic coming from

the main border crossing with Pakistan, at Torkham.

At present, each day some 400 refugee

families come through the encashment center, which as its name suggests is the

place where registered refugees get cash from the UNHCR to start new lives —

about $400 per family member, expected to last them six months.

In 2014, by contrast, only 467 families came

through Samarkhel in the entire year — a busy day’s worth now. After relations

between Afghanistan and Pakistan soured last June, anti-refugee campaigns by

the Pakistani authorities began driving many people to leave.

“We believe if it continues at the same rate

no more Afghans will be left in Pakistan by next July or August,” said Ahmed

Wali, who manages the center for the refugee agency.

Refugees say they have faced a campaign of

police and official harassment in Pakistan ever since relations between the two

countries hit a new low last summer. Among the Afghans who have been suddenly

rounded up on various legal charges, often after decades of residence, was

Sharbat Gula, who became internationally famous as the “Afghan girl” who

appeared on a cover of National Geographic magazine in 1985. A Pakistani court

ordered on Friday that she be deported.

Almost none of the Afghans leaving Pakistan

right now are returning out of any belief that Afghanistan is now safer to live

in. Official pressure and discrimination are the most common reasons given.

Under international law, Pakistan is obliged

to allow registered refugees to stay, and most of those who leave are doing so

voluntarily — in theory. “I personally don’t see this as a voluntary

repatriation,” said Mohammad Ismail, head of the UNHCR office in Jalalabad.

“When you are harassed, intimidated, rounded up by police, taken to court,

forced to pay bribes, you are being forced to leave.”

Shaqiullah, 46, fled the Soviet invasion 29

years ago to Pakistan, at age 17. Last month, he returned with his two wives

and their 20 children, ranging in age from 6 months to 28 years, all born in

Pakistan. He stopped in Samarkhel to collect his reintegration payment before

heading on to Jalalabad.

“They are all sad and unhappy in their new

home,” he said. “They had friends there, schools there, everything there, they

didn’t know anything else.” Shaqiullah is luckier than most, however, since he

is a mullah and has already found a job — as the mullah for a refugee camp in

Afghanistan for newly homeless Afghans.

Undocumented returning refugees, who never

succeeded in being registered as refugees but have often spent years abroad,

are even worse off. Since they are not entitled to UNHCR cash reintegration

payments, the International Organization for Migration screens those who come

back and singles out the 40 percent who are most vulnerable — a sort of triage

brought by funding shortfalls.

Typically, the vulnerable returnees receive

$500 a family, and other emergency services, from I.O.M., which has begun an

emergency appeal to be able to fund even that level of service. UNHCR also says

it is greatly underfunded to help the returnees.

Other than the cash payments, when available,

most of the refugees have little to come home to in Afghanistan. While the

Afghan government has promised them plots of land, that is unlikely to come

about any time soon; internally displaced refugees already have been waiting

for years for such promised land grants to materialize.

“There are more than a million people on the

move,” Ms. Ameratunga said. “And this is happening at a time when winter can be

a life-or-death challenge, and when donor fatigue is stretched with all the

disasters happening all over the world.”

Follow Rod Nordland on Twitter @rodnordland.

Fahim Abed, Zahra Nader and Jawad Sukhanyar

contributed reporting from Kabul, Afghanistan.