[But while the move could avoid the awkwardness of Mr. Clinton jetting around the world asking for money while his wife is president, it did not resolve a more pressing question: how her administration would handle longtime donors seeking help from the United States, or whose interests might conflict with the country’s own.]

By Amy Chozick and Steve Eder

|

|

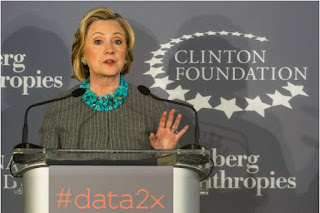

Mrs. Clinton, at a news

conference in 2015, joined the foundation

when she left the state department and

stepped down in 2015 before

beginning her campaign. Credit Andrew

Burton/Getty Images

|

The kingdom of Saudi Arabia donated more than

$10 million. Through a foundation, so did the son-in-law of a former Ukrainian

president whose government was widely criticized for corruption and the murder

of journalists. A Lebanese-Nigerian developer with vast business interests

contributed as much as $5 million.

For years the Bill, Hillary and Chelsea

Clinton Foundation thrived largely on the generosity of foreign donors and

individuals who gave hundreds of millions of dollars to the global charity. But

now, as Mrs. Clinton seeks the White House, the funding of the sprawling

philanthropy has become an Achilles’ heel for her campaign and, if she is

victorious, potentially her administration as well.

With Mrs. Clinton facing accusations of

favoritism toward Clinton Foundation donors during her time as secretary of state,

former President Bill Clinton told foundation employees on Thursday that the

organization would no longer accept foreign or corporate donations should Mrs.

Clinton win in November.

But while the move could avoid the

awkwardness of Mr. Clinton jetting around the world asking for money while his

wife is president, it did not resolve a more pressing question: how her

administration would handle longtime donors seeking help from the United

States, or whose interests might conflict with the country’s own.

The Clinton Foundation has accepted tens of

millions of dollars from countries that the State Department — before, during

and after Mrs. Clinton’s time as secretary — criticized for their records on

sex discrimination and other human-rights issues. The countries include Saudi

Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Oman, Brunei and Algeria.

Saudi Arabia has been a particularly generous

benefactor. The kingdom gave between $10 million and $25 million to the Clinton

Foundation. (Donations are typically reported in broad ranges, not specific

amounts.) At least $1 million more was donated by Friends of Saudi Arabia,

which was co-founded by a Saudi prince.

Saudi Arabia also presents Washington with a

complex diplomatic relationship full of strain. The kingdom is viewed as a

bulwark to deter Iranian adventurism across the region and has been a partner

in the fight against terrorism across the Persian Gulf and wider Middle East.

At the same time, though, American officials

have long worried about Saudi Arabia’s suspected role in promoting a hard-line

strain of Islam, which has some adherents who have been linked to violence.

Saudi officials deny any links to terrorism groups, but critics point to Saudi

charities that fund organizations suspected of ties to militant cells.

Brian Fallon, a spokesman for the Clinton

campaign, said the Clintons and the foundation had always been careful about

donors. “The policies that governed the foundation’s activities during Hillary

Clinton’s tenure as secretary of state already went far beyond legal

requirements,” he said in a statement, “and yet the foundation submitted to

even more rigorous standards when Clinton declared her candidacy for president,

and is pledging to go even further if she wins.”

Mrs. Clinton’s opponent, Donald J. Trump,

could face his own complications if he becomes president, with investments

abroad and hundreds of millions of dollars in real estate debt — financial

positions that could be affected by moves he makes in the White House. And on

Friday, Paul Manafort resigned as chairman of the Trump campaign, in part

because of reports about his lucrative consulting work on behalf of pro-Russian

Ukrainian politicians.

Still, Mr. Trump has seized on emails

released over the past several weeks from Mrs. Clinton’s tenure as secretary of

state, in which a handful of donors are mentioned. He has attacked her over an

email chain that showed Douglas J. Band, an adviser to Mr. Clinton, seeking to

arrange a meeting between a senior American government official and Gilbert

Chagoury, a Lebanese-Nigerian real estate developer who donated between $1

million and $5 million. Mr. Chagoury explained through a spokesman that he had

simply wanted to provide insights on elections in Lebanon.

Some emails and other records described

donors seeking and in some cases obtaining meetings with State Department

officials. None showed Mrs. Clinton making decisions in favor of any

contributors, but her allies fear that additional emails might come out and

provide more fodder for Mr. Trump.

Craig Minassian, a spokesman for the

foundation, said the decision to forgo corporate and foreign money had nothing

to do with the emails. The foundation will continue to raise money from

American individuals and charities.

“The only factor is that we remove the perception

problems, if she wins the presidency,” he said, “and make sure that programs

can continue in some form for people who are being helped.”

But Tom Fitton, the president of Judicial

Watch, a conservative group that has sued to obtain records from Mrs. Clinton’s

time at the State Department, said that “the damage is done.”

“The conflicts of interest are cast in stone,

and it is something that the Clinton administration is going to have to grapple

with,” Mr. Fitton said. “It will cast a shadow over their policies.”

And in an election year in which a majority

of Americans say they do not trust Mrs. Clinton, even some allies questioned

why the foundation had not reined in foreign donations sooner, or ended them

immediately.

A Bloomberg poll in June showed that 72

percent of voters said it bothered them either a lot or a little that the

Clinton Foundation took money from foreign countries while Mrs. Clinton was

secretary of state. In a CNN/ORC International Poll the same month, 38 percent

of voters said Mr. Clinton should completely step down from the foundation,

while 60 percent said he should be able to continue working with the foundation

if his wife became president. Mr. Clinton said Thursday he would leave the

foundation’s board if Mrs. Clinton won.

Edward G. Rendell, a former Democratic

governor of Pennsylvania, said the foundation should be disbanded if Mrs.

Clinton wins, and he added that it would make sense for the charity to stop

taking foreign donations immediately.

“I think they’ll do the right thing,” Mr.

Rendell said, “and the right thing here is, without question, that the first

gentleman have nothing to do with raising money for the foundation.”

Mr. Minassian said ending foreign fund-raising

before other sources of money could be found, and without knowing who will win

the election, could needlessly gut programs that help provide, for instance,

H.I.V. medication to children in Africa.

Begun in 1997, the foundation has raised roughly

$2 billion and is overseen by a board that includes Mr. Clinton and the

couple’s daughter, Chelsea. Mrs. Clinton joined when she left the State

Department and stepped down in 2015 before beginning her campaign. Its work

covers 180 countries, helping fund more than 3,500 projects.

Having a former president at the helm proved

particularly productive, with foreign leaders and business people opening their

doors — and their wallets — to the preternaturally sociable Mr. Clinton.

Among the charity’s accomplishments: Its

Clinton Health Access Initiative — which is run by Ira C. Magaziner, who was a

White House aide involved in Mrs. Clinton’s failed effort to overhaul the

health care system in her husband’s first term — renegotiated the cost of

H.I.V. drugs to make them accessible to 11.5 million people. The foundation

helped bring healthier meals to more than 31,000 schools in the United States,

and it has helped 105,000 farmers in East Africa increase their yields,

according to the foundation’s tally.

In December 2008, shortly before Mrs. Clinton

became secretary of state, Mr. Clinton released a list of more than 200,000

donors to defuse speculation about conflicts.

Soon after, Mrs. Clinton agreed to keep

foundation matters separate from official business, including a pledge to “not

participate personally and substantially in any particular matter that has a

direct and predictable effect upon” the foundation without a waiver. The Obama

White House had particularly disliked the gatherings of world leaders,

academics and business people, called the Clinton Global Initiative, that the

foundation was holding overseas. The foundation limited the conferences to

domestic locations while Mrs. Clinton was secretary of state. On Thursday, Mr.

Clinton said the gathering in September in New York would be the foundation’s

last.

One of the attendees at these conferences

speaks to the stickiness of some donor relationships.

Victor Pinchuk, a steel magnate whose

father-in-law, Leonid Kuchma, was president of Ukraine from 1994 to 2005, has

directed between $10 million and $25 million to the foundation. He has lent his

private plane to the Clintons and traveled to Los Angeles in 2011 to attend Mr.

Clinton’s star-studded 65th birthday celebration.

Between September 2011 and November 2012,

Douglas E. Schoen, a former political consultant for Mr. Clinton, arranged

about a dozen meetings with State Department officials on behalf of or with Mr.

Pinchuk to discuss the continuing political crisis in Ukraine, according to

reports Mr. Schoen filed as a registered lobbyist.

“I had breakfast with Pinchuk. He will see

you at the Brookings lunch,” Melanne Verveer, a Ukrainian-American then working

for the State Department, wrote in a June 2012 email to Mrs. Clinton.

A previously undisclosed email obtained by

Citizens United, the conservative advocacy group, through public records

lawsuits shows the name of Mr. Pinchuk, described as one of Ukraine’s “most

successful businessmen,” among those on an eight-page list of influential

people invited to a dinner party at the Clintons’ home.

Earlier in 2012, Ambassador John F. Tefft

wrote to Mrs. Clinton about a visit to Ukraine by Chelsea Clinton and her

husband, Marc Mezvinsky, “at the invitation of oligarch, Victor Pinchuk.” Mrs.

Clinton replied, “As you know, hearing nice things about your children is as

good as it gets.”

In July 2013, the Commerce Department began

investigating complaints that Ukraine — and by extension Mr. Pinchuk’s company,

Interpipe — and eight other countries had illegally dumped a type of steel tube

on the American market at artificially low prices.

A representative for Mr. Pinchuk said the

investigation had nothing to do with the State Department, had started after

Mrs. Clinton’s tenure and been suspended in July 2014. He added that at least

100 other people had attended the dinner party at Mrs. Clinton’s house and that

she and Mr. Pinchuk had spoken briefly about democracy in Ukraine.

A deal involving the sale of American uranium

holdings to a Russian state-owned enterprise was another example of the foundation

intersecting with Mrs. Clinton’s official role in the Obama administration. Her

State Department was among the agencies that signed off on the deal, which

involved major Clinton charitable backers from Canada.

There was no evidence that Mrs. Clinton had

exerted influence over the deal, but the timing of the transaction and the

donations raised questions about whether the donors had received favorable

handling.

Even if Mr. Clinton steps down, there could

be remaining complications about a potential president’s name being affixed to

an international foundation. And Chelsea Clinton, who is its vice chairwoman,

would continue her leadership role.

“It is very difficult to see how the

organization called the Clinton Foundation can continue to exist during a

Clinton presidency without that posing all sorts of consequences,” said John

Wonderlich, the interim executive director of the Sunlight Foundation, a

government watchdog group in Washington. “What they announced only addresses

the most egregious potential conflicts.”

Considering the scale and scope of the

foundation, Mr. Wonderlich said it was easy to “name a hundred different types

of conflicts.”

The reality is, he added, “there are no

recusals when you are president.”

Kitty Bennett contributed research.