[In

the case of Bangladesh Bank, the thieves used stolen credentials to try to

transfer nearly $ 1 billion of the central bank’s money at the New York Fed to

accounts around the world. About $81 million was ultimately transferred, to

casinos in the Philippines, where much of it disappeared.]

By Megha Bahreejune

|

|

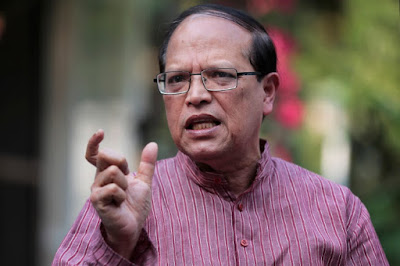

Atiur Rahman resigned as

governor of Bangladesh’s central bank after $ 81 million

was stolen in

February.CreditA.M. Ahad/Associated Press

|

DHAKA,

Bangladesh — The former

governor of Bangladesh’s central bank, from which $81 million was stolen in

February, says that flaws in the global money transfer system — and not any

misstep by him — are to blame for the brazen cyberheist.

In an interview this week at his home in a

well-to-do neighborhood in the Bangladeshi capital, Dhaka, Atiur Rahman, who

resigned from his post after the theft, said that the loss had been a “systemic

failure” and that “Bangladesh should not be blamed for something going wrong in

the chain.”

In particular, he blamed the Federal Reserve

Bank of New York, whereBangladesh’s central bank had placed the money.

“If you want to take $500 out of your account

in the U.S., you’ll be asked several questions,’’ Mr. Rahman said. “But here,

millions are going, and you’re not asking any questions.” The New York Fed, he

added, “should have immediately called someone in Bangladesh — the governor or

someone.”

Mr. Rahman also said that he tapped a

cybersecurity firm a year ago to help the bank bulk up its defenses but that it

had been hired only after the theft because of bureaucratic delays.

Mr. Rahman’s comments go to the heart of

fears in the international banking community. The theft exposed weaknesses in

the way the world’s banks, companies and other financial institutions transfer

money around the globe. Swift — the system they use to move that money and

through which the money was transferred out of the New York Fed — has since

said it has seen other such attempts to steal money from the global banking

system.

In the case of Bangladesh Bank, the thieves

used stolen credentials to try to transfer nearly $ 1 billion of the central

bank’s money at the New York Fed to accounts around the world. About $81

million was ultimately transferred, to casinos in the Philippines, where much

of it disappeared.

A spokeswoman for the New York Fed declined

to comment on Mr. Rahman’s remarks but said that the theft had not been the

result of a breach of its computer systems.

Some experts have said the theft was the

result of weaknesses in Bangladesh Bank itself. Local news reports have said

the bank used $10 routers and no firewalls. But Mr. Rahman disputed the notion

that the bank’s digital security was lax.

“I made cybersecurity the top of the agenda,”

he said, adding, “I smelt a year back that this could be a problem. It was my

bad luck that this happened now.”

He said that the bank had tapped Mandiant, a

cybersecurity firm owned by FireEye Inc. of the United States, as an adviser

before the theft, but that bureaucratic tangles in Bangladesh had kept Mandiant

from fully joining until after the incident.

Swift executives have also been frustrated

that some of its users have been slow to disclose a breach in their systems and

— in one case — failed to inform the consortium of an attack at all. Swift

representatives have suggested to federal officials in the United States that

banks that cannot maintain a basic level of cybersecurity may have to be

removed from the network, a decision that could economically marginalize

certain parts of the world.

A spokeswoman for Swift — which stands for

Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication — declined to

comment on Mr. Rahman’s remarks but said: “Security weaknesses at individual

customer firms have an impact on others in the wider financial system, which

means that the industry as a whole has to respond by renewing and enhancing its

security.”

Mr. Rahman said that an investigation was

continuing and that there might have been negligence at Bangladesh Bank. But he

said he was not responsible for any wrongdoing. “As a governor, I’m not

supposed to look at each and every small thing,” he said.

“Maybe someone’s password was compromised,”

he added. “It was a departmental failure and not the fault of the governor. It

was a high dosage attack, like a 15 on the Richter scale attack. Other parties

could have helped or warned Bangladesh. You cannot imagine my shock.”

On speculation that someone within the bank

had actively helped the thieves, he said, “if there’s a criminal, catch him,

but without blaming anyone without reason.”

Mr. Rahman resigned after the theft for the

greater good of the bank, he said. But he defended his conduct in the aftermath

of the theft. The former governor has been criticized in Bangladesh for not

reporting the theft to the country’s government for a month.

“I wanted to save the financial system and

the image of the country,” he said.

“It could be a mistake, but it was not a

crime,” he said, adding, “people should not expect that I’ll be technically so

smart that I would know from the start what happened.”

To steal the money, the thieves sent transfer

orders to the New York Fed using the Bangladesh Bank’s credentials. The heist

was well timed — it took place during Thursday night in Bangladesh, on the eve

of the country’s weekend. When workers there discovered the transfers on

Saturday, they tried to reach the New York Fed, which was closed for its

weekend.

Mr. Rahman contends that the New York Fed did

not do enough to verify that the orders were real. “There was a terrible lack

of efficiency from the Fed,” he said. “We were sending mails, faxes, but there

was no one to pick that up. We need a hotline.”

In May, representatives of the Fed, of

Bangladesh Bank and of Swift met in Basel, Switzerland, to discuss protecting

the global financial system from these types of attacks.

Mr. Rahman also laid some of the blame on the

Philippines, where the theft has exposed what critics say are holes in efforts

to counter money laundering. “If the Fed really wants to help, it only needs to

make one small phone call to the Philippines central bank governor and order it

to return the money,” he said. “It’s the credibility of the system that’s at

stake.”

In March, the agency that tackles money

laundering in the Philippines filed criminal charges against two businessmen,

accusing them of breaking the country’s money-laundering laws by receiving some

of the money from the heist.

A spokeswoman for the governor of the

Filipino central bank, Amando Tetangco Jr., wrote in an email, “charges have

been filed against those who have been identified as being involved in the

Bangladesh heist. We await the decision of the courts.”

Michael Corkery contributed reporting from

New York.