[Members of the Assyrian diaspora have called for international intervention, and on Thursday, warplanes of the United States-led coalition struck targets in the area, suggesting that the threat to a minority enclave had galvanized a reaction, as a similar threat did in the Kurdish city of Kobani last year.]

By Anne Barnard

|

|

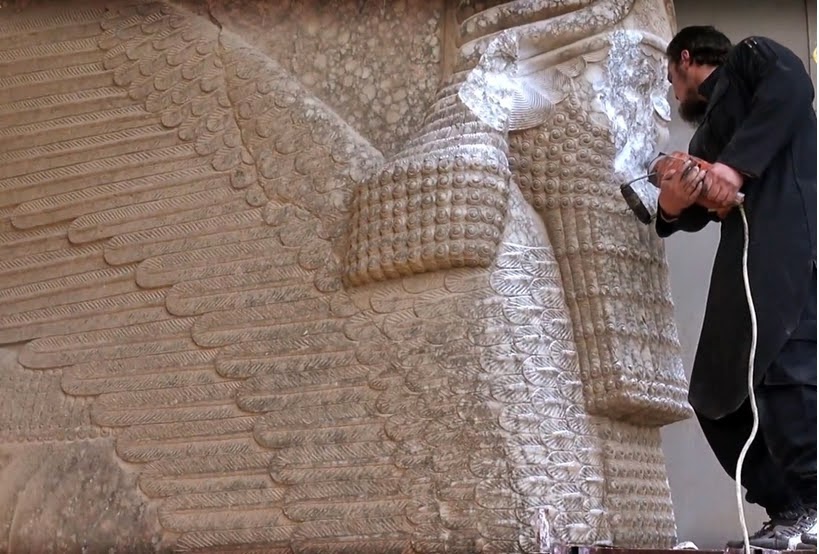

An ISIS video showed the

destruction of ancient Assyrian artifacts in Mosul, Iraq.

Credit -/Agence

France-Presse — Getty Images

|

ISTANBUL — The reports are like

something out of a distant era of ancient conquests: entire villages emptied,

with hundreds taken prisoner, others kept as slaves; the destruction of

irreplaceable works of art; a tax on religious minorities, payable in gold.

A rampage reminiscent of

Tamerlane or Genghis Khan, perhaps, but in reality, according to reports by

residents, activist groups and the assailants themselves, a description of the

modus operandi of the Islamic State’s self-declared caliphate this week. The

militants have prosecuted a relentless campaign in Iraq and Syria against what

have historically been religiously and ethnically diverse areas with traces of

civilizations dating to ancient Mesopotamia.

The latest to face the

militants’ onslaught are the Assyrian Christians of northeastern Syria,

one of the world’s oldest Christian communities, some speaking a modern version

of Aramaic, the language of Jesus.

Assyrian leaders have

counted 287 people taken captive, including 30 children and several dozen

women, along with civilian men and fighters from Christian militias, said

Dawoud Dawoud, an Assyrian political activist who had just toured the area, in

the vicinity of the Syrian city of Qamishli. Thirty villages had been emptied,

he said.

The Syriac Military

Council, a local Assyrian militia, put the number of those taken at 350.

Reached in Qamishli, Adul

Ahad Nissan, 48, an accountant and music composer who fled his village before

the brunt of the fighting, said a close friend and his wife had been captured.

“I used to call them

every other day. Now their mobile is off,” he said. “I tried and tried. It’s so

painful not to see your friends again.”

Members of the Assyrian

diaspora have called for international intervention, and on Thursday, warplanes

of the United States-led coalition struck targets in the area, suggesting that

the threat to a minority enclave had galvanized a reaction, as a similar threat

did in the Kurdish city of Kobani last year.

The assault on the

Assyrian communities comes amid battles for a key crossroads in the area. But

to residents, it also seems to be part of the latest effort by the Islamic State

militants to eradicate or subordinate anyone and anything that does not comport

with their vision of Islamic rule — whether a minority sect that has survived

centuries of conquerors and massacres or, as the world was reminded on

Thursday, the archaeological traces of pre-Islamic antiquity.

An Islamic State video showed the militants

smashing statues with sledgehammers inside the Mosul Museum, in

northern Iraq, that showcases recent archaeological finds from the ancient

Assyrian empire. The relics include items from the palace of King Sennacherib,

who in the Byron poem “came down like the wolf on the fold” to destroy his

enemies.

“A tragedy and

catastrophic loss for Iraqi history and archaeology beyond comprehension,” Amr

al-Azm, the Syrian anthropologist and historian, called the destruction on his

Facebook page.

“These are some of the

most wonderful examples of Assyrian art, and they’re part of the great history

of Iraq, and of Mesopotamia,” he said in an interview. “The whole world has

lost this.”

Islamic State militants

seized the museum — which had not yet opened to the public — when they took

over Mosul in June and have repeatedly threatened to destroy its collection.

In the video, put out by

the Islamic State’s media office for Nineveh Province — named for an ancient

Assyrian city — a man explains, “The monuments that you can see behind me are

but statues and idols of people from previous centuries, which they used to worship

instead of God.”

A message flashing on the

screen read: “Those statues and idols weren’t there at the time of the Prophet

nor his companions. They have been excavated by Satanists.”

The men, some bearded and

in traditional Islamic dress, others clean-shaven in jeans and T-shirts, were

filmed toppling and destroying artifacts. One is using a power tool to deface a

winged lion much like a pair on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in

New York.

The Islamic State, also

known as ISIS or ISIL, has presented itself as a

modern-day equivalent of the conquering invaders of Sennacherib’s day, or as

Islamic zealots smashing relics out of religious conviction.

Yet in the past, the

militants have veered between ideology and pragmatism in their relationship to

antiquity — destroying historic mosques, tombs and artifacts that they consider

forms of idolatry, but also selling more portable objects to fill their

coffers.

The latest eye-catching

destruction could have a more strategic aim, said Mr. Azm, who closely follows

the Syrian conflict and opposes both the Islamic State and the government.

“It’s all a provocation,”

he said, aimed at accelerating a planned effort, led by Iraqi forces and backed

by United States warplanes, to take back Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city.

“They want a fight with

the West because that’s how they gain credibility and recruits,” Mr. Azm said.

“They want boots on the ground. They want another Falluja,” a reference to the

2004 battle in which United States Marines, in the largest ground engagement

since Vietnam, took that Iraqi city from Qaeda-linked insurgents whose

organization would eventually give birth to the Islamic State.

The Islamic State has

been all-inclusive in its violence against the modern diversity of Iraq and

Syria. It considers Shiite Muslims apostates, and has destroyed Shiite shrines

and massacred more than 1,000 Shiite Iraqi soldiers. It has demanded that

Christians living in its territories pay the jizya, a tax on religious

minorities dating to early Islamic rule.

Islamic State militants

have also slaughtered fellow Sunni Muslims who reject their rule, killing

hundreds of members of the Shueitat tribe in eastern Syria in

one clash alone. They have also massacred and enslaved members of the Yazidi

sect in Iraq.

The latest to face its

wrath, the Assyrian Christians, consider themselves the descendants of the

ancient Assyrians and have survived often bloody Arab, Mongolian and Ottoman

conquests, living in modern times as a small minority community periodically

under threat. Thousands fled northern Iraq last year as Islamic State militants

swept into Nineveh Province.

Early in February,

according to Assyrian groups inside and outside Syria, came a declaration from

the Islamic State that Christians in a string of villages along the Khabur

River in Syrian Hasaka Province would have to take down their crosses and pay

the jizya, traditionally paid in gold.

That prompted some to

flee, and others to take a more active part in fighting ISIS alongside Kurdish militias, helping

take back some territory.

Islamic State militants

hit back, hard, driving more than 1,000 Assyrian Christians from their homes,

some crossing the Khabur River, a tributary of the Euphrates, in small boats by

night.

Local Assyrian leaders

were negotiating with the Islamic State through mediators, said Mr. Dawoud, the

deputy president of the Assyrian Democratic Organization. The Assyrian

International News Agency, a website sharing community news, said Arab tribal leaders

were mediating talks to exchange the prisoners for captured Islamic State

fighters and that the Islamic State had agreed to free Christian civilians but

not fighters.

Mr. Nissan, the

accountant, described how he and others crammed into a truck, paying exorbitant

rates, to escape. Earlier, he said, Nusra Front fighters and other Syrian

insurgents had looted the village without harming anyone, but he feared ISIS

more because “they consider us infidels.”

“I made a vow, when I

return I want to kiss the soil of my village and pray in the church,” he said,

adding that he had composed a song for the residents of Nineveh Province when

they were displaced a few months ago.

“I called it ‘Greetings

from Khabur to Nineveh,’ “ he said. “Now we’re facing the same scenario.”

Hwaida Saad and Maher

Samaan contributed reporting from Beirut, Lebanon, and Karen Zraick from New

York.