[In 2004, the

government introduced the National Pension System, or N.P.S. It marked a

radical transformation from the government’s benefits-based pension program to

one in which employees contribute toward their own retirement funds while

employed. The new system affects people employed in the federal government

after 2004, with the exception of India’s armed forces, who are part of a

separate pension system. State government employees in 27 out of 28 Indian

states have also been brought under its ambit, according to a government

release.]

|

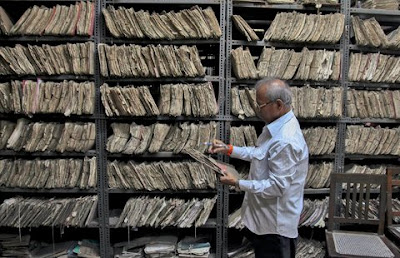

| Divyakant Solanki/European Pressphoto AgencyA government employee of the telegraph department at his workplace in Mumbai, Maharashtra, on July 15. |

Ashwini Kumar Sharma, 60, a data processing assistant with India’s

Ministry of Home Affairs, is about to retire after 41 years of working with the

government. After retirement, he will receive a monthly pension that will equal

half the last salary from his employer. He will get to withdraw the money that

a mandatory government program made him set aside during his working years,

along with the interest it accrued in a savings account.

Mr. Sharma will also

be given a certain sum, known as “gratuity”— a token of gratitude for decades

of service.

“Pension gives me a

sense of security,” said Mr. Sharma, who is retiring at the end of September.

“I am not worried about eating two square meals a day after I retire.”

He is one of India’s

estimated 90 million elderly, defined as those 60 years and older, according to

a United Nations report.

By 2050 that number is expected to rise to 315 million.

India does not have a

universal social security plan for its 1.2 billion people. The pension

system covers only about 12 percent of the working population, according

to India’s Ministry of Finance.

In 2004, the

government introduced the National Pension System, or N.P.S. It marked a

radical transformation from the government’s benefits-based pension program to

one in which employees contribute toward their own retirement funds while

employed. The new system affects people employed in the federal government

after 2004, with the exception of India’s armed forces, who are part of a

separate pension system. State government employees in 27 out of 28 Indian

states have also been brought under its ambit, according to a government

release.

A regulatory body

created in 2003 that manages the new retirement savings package will be given

legal status once India’s president signs into law a bill known as thePension Fund

Regulatory and Development Authority Bill, 2011. The Indian

Parliament approved the draft law earlier this month, after amending some

provisions of the existing bill, but its details are not

public.

The draft legislation

was aimed at reforming the pension sector, limiting government’s pension

liabilities in the long run and expanding the social security safety net for

the national population.

In the current

financial year, which begun in April and ends March 2014, the government has budgeted 30,000

crore, or 30 billion rupees ($473 million), for pensions and other retirement

benefits for employees who continue to be part of the old pension system, which

is indexed to inflation — the pension amount will increase whenever the

government revises salaries due to high inflation.

Foreign companies will

be allowed to hold up to a 26 percent stake in Indian businesses selling

pension products once the law goes into effect.

The new pension system

was extended to the non-government sector in 2009. Most companies in the

private sector with a staff of at least 20 people are required by law to

participate in a savings plan run by a government organization, known as the Employees’

Provident Fund Organization. Under this program, a small portion of an

employee’s salary with a matching contribution from the employer is put into a

pension plan and long-term savings that accrue interest, at a rate which is

revised by the government every year.

According to the statistics released

by the Indian ministry of labor and employment in 2011, 26 million people work

in the organized public and private sectors in India, while 433 million Indians

work in the unorganized sector, a figure that includes daily wage laborers and

workers at smaller businesses and a host of other jobs.

Since the informal

sector is loosely structured, the existing pension programs are not mandatory

for them, creating a need for reform.

“It was realized that

people in the unorganized sector did not think of pension savings,” said Ashvin

Parekh, a senior expert adviser at Ernst & Young consulting firm in Mumbai,

Maharashtra, explaining that now they can voluntarily participate in the new

pension system.

Keshav Sharma, 28,

followed in the footsteps of his father, Ashwini Kumar Sharma, by taking a job

with the Indian government after Keshav left his job at a privately-run IT

start up.

“The government job

offers better security,” said the younger Mr. Sharma, who now works as an

assistant section officer in India’s Ministry of Defense.

Yet he was unsure of

the merits of the government’s new pension program. The younger Mr. Sharma

contributes 10 percent of a portion of his monthly salary; his employer makes

an equal contribution. The aggregated amount is put into a pension account and

invested in market-driven pension products sold by three public sector

financial institutions chosen by the Pension Fund Regulatory and Development

Authority, or PFRDA. A total of eight companies, including five from the

private sector, have been enlisted as fund managers by the pension regulator.

“I keep asking myself

whether this plan is a good or a bad thing for us,” he said. “It is a

market-driven program. I don’t know how much I will get on my retirement.”

Every month, money

gets deducted from a government employee’s salary and designated financial

institutions then invest the funds in equities, government securities and debt

including corporate bonds. They invest the money on the employees’ behalf under

rules established by the regulator.

“We are not consulted

before our money is invested,” the younger Mr. Sharma said.

An employee of LIC

Pension Fund Limited, who was not authorized to speak to the media, said the

savings of government workers are divided between the LIC, SBI Pension Funds

Private Limited and UTI Retirement Solutions Limited.

“The funds are routed

through an authorized bank to each of these companies, which handles a corpus

of funds, not individual accounts.” The money is then invested according to the

PFRDA guidelines, the employee said.

Every person signed up

for the new pension program is given a “permanent retirement account number”

that can be used to track the investments and the interest and other earnings

from the money. Mr. Sharma said that at present, the online account does not

allow a government employee to switch to a different pension product or change

a fund manager.

“What if a company our

money is being invested in goes bankrupt?,” he asked. “We will lose all our

savings.”

Officials acknowledge

that there are always inherent risks to investing in such funds.

“The basic axiom for

investment is no risk, no gain,” said Yogesh Agarwal, the chairman of the

PFRDA.

Mr. Agarwal is

convinced that once the pension draft legislation is signed into law, it will

ameliorate the anxieties about the National Pension System.

“It will instill

confidence in people about the pension product, and ensure superior return on

investments,” he said.

The PFRDA touts the

National Pension System as the cheapest pension product in India offering high

returns. In the financial year that ended March, the returns on the plans

offered under this program ranged between 12 to 14 percent, Mr. Agarwal said.

A minimum annual

contribution of 6,000 rupees, or $95, is required to keep the pension account

open, and it is portable across jobs. On retirement, 60 percent of the money

can be withdrawn and the remaining 40 percent has to be reinvested in life

insurance products sold by companies authorized by the PFRDA. If someone makes

withdrawals before reaching age 60, only 20 percent of the savings can be taken

out, although the recent amendments in the draft legislation made a push for

that percentage to go up to 25.

The regulator has

registered 5.2 million subscribers and accumulated almost 35,000 crore, or 35

billion rupees ($552 million) in contributions since 2004, according tofigures released in

August.

Mr. Agarwal of PFRDA

said that in the old defined benefits system, government employees are paid

through the current year’s government revenue, a fiscally dangerous practice.

The defined contributions system allows the government to rectify its mistake

of “funding its own liability,” he said.

Even with the

introduction of the new law, the government will not be able to offset its

pension liability for at least the next few decades, experts say.

“The idea of pension

is to reduce uncertainty, vulnerability and poverty in old age,” said Mukesh

Anand, an assistant professor at the National Institute of Public Finance and

Policy in New Delhi. “But the new bill doesn’t address the core

objectives of pension.”

He added that the

government was trying to shift the burden of paying for pensions from the

public system to the individual.

The new pension

package, which the government is trying to sell to the non-government sector,

faces stiff competition from other pension products already available in the

market. Mr. Parekh of Ernst & Young estimates it to be a $7 billion market.

He described the National Pension System as the cheapest product available, but

said that it is the returns that matter and not the cost.

“There are 38-40 other

financial instruments available in the market, the N.P.S. does not compare too

well with them,” he said referring to other investment options.

Pointing to one of the

shortcomings of the new pension system, he said, “The architecture is all

wrong. The beneficiary is so remote from fund managers.”

Mr. Parekh expects the

pension sector to grow substantially as the life expectancy of Indians

increases.

“Rising income levels

will lead people to think: ‘If I were to live longer, what will become of me,’”

he said.